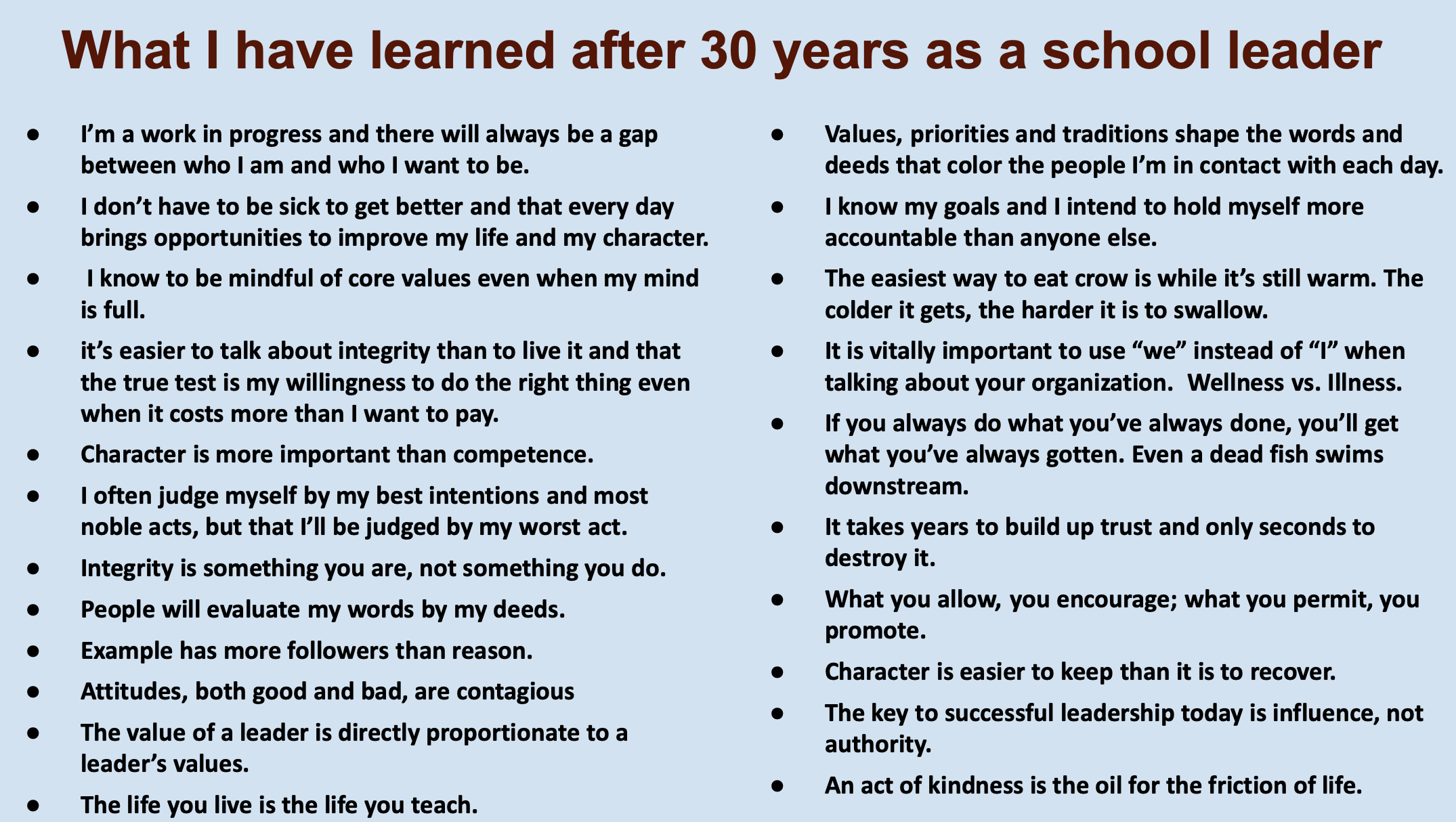

A principal plays a pivotal role in the successful implementation of a CHARACTER COUNTS! initiative. This brief video lesson will share specific strategies to help in defining a school leader’s role in making a difference in not only the character development of students but in the promotion or enhancement of a positive school climate.

School Principals Shape Students’ Values Via School Climate

Over time, students’ personal values become more similar to those of their school principal, according to research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science. The findings indicate that principals’ values are linked with aspects of school climate which are, in turn, linked with students’ own values.

“Given the vast amount of time children spend in school, it is important to assess the impact that schools have on children, beyond their impact on children’s academic skills,” say researchers Yair Berson (New York University and Bar-Ilan University) and Shaul Oreg (Cornell University and The Hebrew University of Jerusalem). “Our findings show that schools contribute to the formation of children’s values.” Although there is a wealth of data showing relationships between aspects of the school environment and students’ academic achievement, relatively little is known about the effects of school climate on non-academic outcomes. Based on previous research investigating leaders’ influence on organizational culture and employees’ values, Berson and Oreg hypothesized that school principals might similarly influence school climate and students’ values over time.

Focusing on four well-established categories of values — self-enhancement, self-transcendence, openness to change, and conservation — school principals filled out a questionnaire in which they read statements about a hypothetical individual and rated how closely they aligned with their own values.

Self-enhancement values were captured in achievement-focused statements (e.g., “Being successful is important to him”), whereas self-transcendence values were depicted in statements highlighting benevolence (e.g., “She goes out of her way to be a dependable and trustworthy friend.”). Values indicating openness to change were conveyed in statements related to preference for stimulation and self-direction (e.g., “She thinks it is important to have all sorts of new experiences,” “Being creative is important to him”). Conservation-related values were demonstrated in statements that covered conformity, tradition, and security (e.g., “It is important to him to follow the rules even when no one is watching,” “It is important to her to maintain traditional values and beliefs,” “Having order and stability in society is important to her”).

At the same time, students completed age-appropriate measures that tapped into the same values. The students completed values measures again two years later. Teachers completed a survey measure focused on aspects of school climate that corresponded with the four values, including the degree to which school climate reflects an emphasis on stability (conservation values), support (self-transcendence values), innovation (openness-to-change values), and performance (self-enhancement values). Teachers also rated the degree to which students in their homeroom displayed various behaviors that reflected the same values.

The researchers found that students’ values became more similar to those of their principal over the two-year study period. “Principals’ personal outlook on life is reflected in the overall school atmosphere, which over time becomes reflected in schoolchildren’s personal outlook and eventual behavior,” Berson and Oreg explain in their paper.

“Values that have to do with maintaining the status quo — emphasizing tradition, conformity and security – showed a different pattern, whereby principals’ values are associated with children’s values, but without the mediating role of the school climate,” say Berson and Oreg.